THE GENDER PAIN GAP

The seven year wait for endometriosis diagnosis in women

“It took over 5 years, well into adulthood and being sexually active with constant pain, for doctors to take my condition seriously” - Josephine Bull

Women are waiting an average of seven years to receive a diagnosis of endometriosis, which is a condition that affects one in nine Australian women.

What is endometriosis?

Endometriosis is a debilitating chronic condition, where the inner lining of the uterus grows outside the uterus. This often results in severe pelvic pain. Currently, endometriosis affects one in nine Australian women, who on average, wait seven years for a diagnosis.

The process for diagnosis and treatment for endometriosis has been a long and painful one for a lot of women.

As her GP was very familiar with endometriosis, and with her family history of the condition in addition to polycystic ovarian syndrome, she made it imperative to do what she could to help Victoria access treatment.

27-year-old PhD student Caitlin Victoria says she was one of the lucky ones.

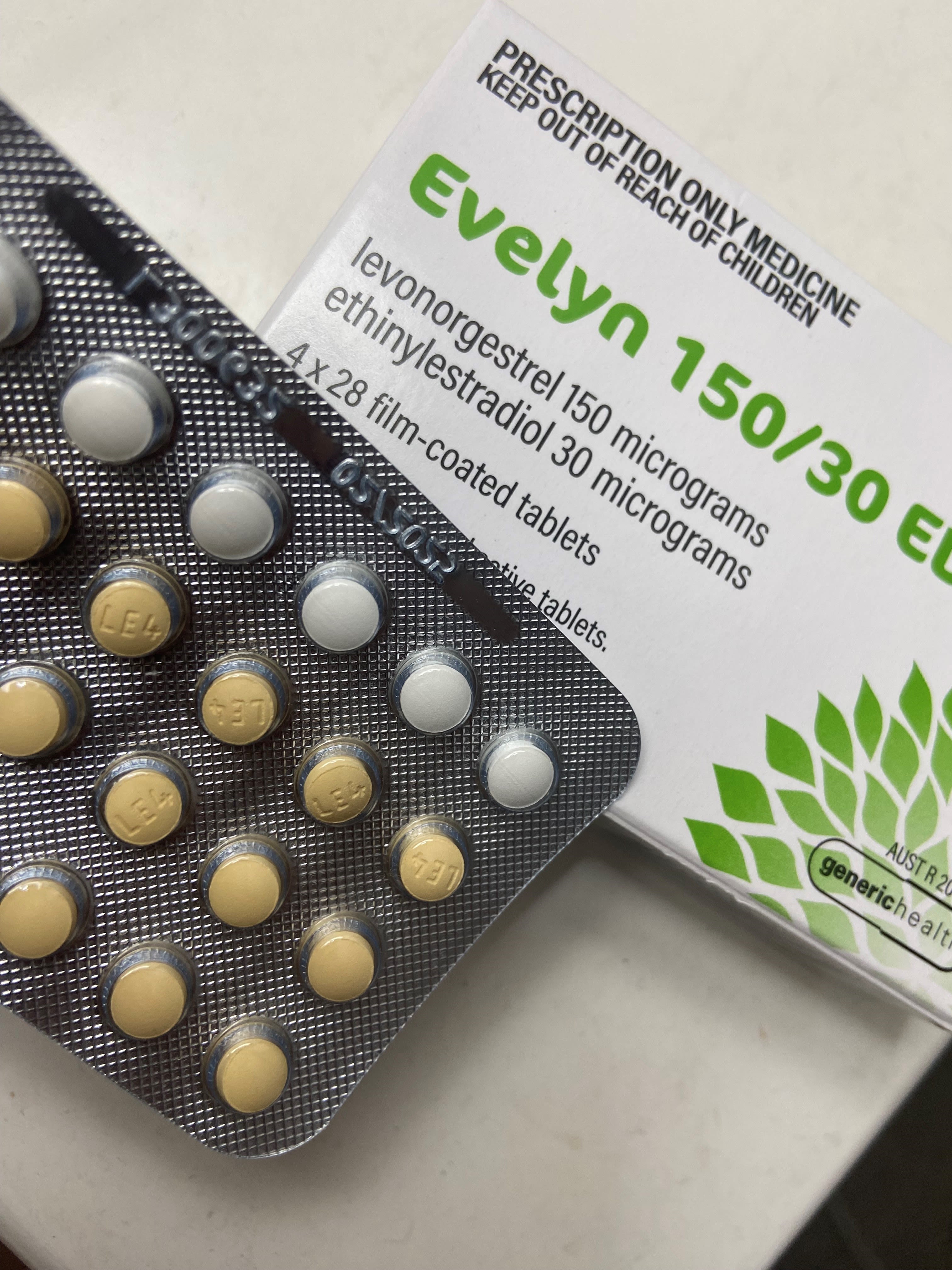

She says that her general practitioner immediately referred her onto a gynaecologist, where she underwent diagnostic ultrasounds, explorative surgery and prescribed hormonal medication for symptom management.

This was after a few months of experiencing a menstrual cycle, where she did not know the unbearable pain she was experiencing, was not normal.

“I remember there were times that I would be completely immobilised, the pain was so bad. My mum also has endometriosis, so she knew that something was wrong,” Victoria states.

“I know I am an outlier; I know most women do not get diagnosed as quickly as I have, nor have their symptoms taken seriously by their doctors” - Victoria

This quick diagnosis rate was not the same for Josephine Bull, a 22-year-old psychology student, who waited five years for a diagnosis.

Since the onset of her first menstrual cycle when she was 14, Bull describes experiencing irregular and heavy periods, with extreme migraines and pelvic pain.

She says that she felt as though her doctors did not take her symptoms seriously, explaining it felt difficult to get them to explain further.

She had to take multiple days a week off school and work because the pain was so relentless, her bouts of pain sharp, stabbing and burning.

“It took over five years, well into adulthood and being sexually active with constant pain, for doctors to take my condition seriously” - Josephine Bull

Bull was advised by doctors to take over the counter pain relief, exercise and eat well to manage her severe pain.

“It took over five years, well into adulthood and being sexually active with constant pain for doctors to take my condition seriously,” says Bull.

Once she was able to receive diagnosis and undergo treatment, the out-of-pocket cost was overwhelming.

What is the cost?

“I have paid $500 out of pocket for each laparoscopy surgery, $150 for ultrasounds beforehand and $200 for gynecologist consultations. This was all with private health insurance, not to mention my contraceptive pill and IUD insertion,” Bull says.

Endometriosis costs the Australian economy $6 billion a year.

Bull needs to undergo a laparoscopy every two years, this is a surgical procedure to remove endometrial tissue from outside the uterus.

"I honestly felt really exasperated most of the time, my mental health started to decline, and I felt really depressed over everything piling on top of one another," Bull says.

The combination of cost of treatment, difficulty in getting diagnosed and debilitating pain which still affects Bull, has resulted in the decline of her mental health too.

But the government is trying to do something.

The National Action Plan for Endometriosis

The aim of the initiative is to fund research, education, and awareness programs, and improve clinical management and care.

The government has worked closely with endometriosis experts to develop the ‘National Action Plan for Endometriosis’ which acts as the guidelines for improving outcomes for women across six criteria.

A notable way the government is doing this, is by implementing 22 endometriosis and pelvic pain clinics across the country.

The aim of these clinics is to improve diagnosis, treatment and make care more accessible and affordable to women with endometriosis.

The Assistant Minister for Health and Aged Care GED Kearney said in at the launch in 2023, “we want women to know they can seek care and support at these clinics, that they will be believed and there are treatment options available to them”.

There are currently 22 of these clinics across the country, with at least one in every state or territory.

Each clinic has gained a $700,000 donation toward implementing new equipment, support, training and development over a four-year time frame.

There are currently 22 of these clinics across the country, 7 in NSW alone, but none in the Newcastle or Hunter region.

The government has worked closely with endometriosis experts to develop the ‘National Action Plan for Endometriosis’ which acts as the outline for improving outcomes for women across 6 criteria.

What is the 6 criteria?

1. Developing endorsed endometriosis living guidelines.

2. Improving access to healthcare, including assessment, support, diagnosis, pain management etc.

3. Embedding a school menstrual education program.

4. Increasing the base-level understanding of healthcare professionals.

5. Increase availability of optimal care pathways.

6. Significant expansion into endometriosis research.

Whilst acknowledging that this is a great initiative, Victoria feels disappointed that she would not be able to access its services due to the geographical distance of clinics.

Why are there no clinics in Newcastle?

The Primary Health Network says they have prioritised these clinics to be available to higher concern populations.

The closest EPP clinic is Leichardt General Practice in Central/Eastern Sydney, almost 2 hours away.

Newcastle, and the women with endometriosis and pelvic pain who live there, miss out on being considered a priority.

Has anything changed?

Delayed diagnosis and the debilitating pain of endometriosis remains a persistent issue for women across Australia.

Whilst these endometriosis and pelvic pain clinics offer a glimmer of hope for women like Victoria and Bull who are affected by the condition, clinic locations prevent accessibility to all.

By Mackenzie Reeves